Sunday, August 17, 2008

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

This is the end...

Tim Golden asked me a few weeks ago for my end-of-TFA thoughts. This blog has been gathering dust in the corner. You'll have to excuse me: TFA was keeping me busy in Houston all summer, and then, suddenly, things were over.

I've always struggled with endings. Last summer, I don't think I wrote about the act leaving South Dakota until I actually came back to the state again in the fall. But yesterday, feeling a little bit nostalgic for my Teach For America days, I made my way to Edison High School in North Philly to see how Institute is going in these parts; I figured that was as good an occassion as any to reflect on what happened, and what comes next.

I get the same questions repeatedly. Even the CMAs I talked to yesterday wanted to know: how did I like it? Which is open to broad interpretation, of course. Their follow-up of So you didn't go crazy? makes it a little more clear.

My practiced response--the one that garnered the question on sanity--is that I loved South Dakota, but teaching not so much. I'll certainly miss the inherent adventurousness of my lifestyle in the country, and the people that I adventured with. I won't miss writing tests, or writing lesson plans, or the pressure that came with teaching--or at least the pressure that I put on myself. And I wasn't really there to adventure; I was there to teach.

So perhaps a more important question would be did I teach? I've been indoctrinated by TFA to believe that if the results don't show learning, then there's no teaching. I believe I enumerated the results of my final exams in an earlier post; suffice to say they weren't pretty. During a professional evaluation with my school director at Institute this summer, she remarked that I was sometimes over-critical of my teaching experience. It was feedback I had anticipated, but no matter how I spin the experience, I know I'll never be satisfied with my performance. There was too much more I could have done.

Not to say that there is no positive spin. At my end-of-year conversation, my Program Director told me that despite the low performance of my students, the organization still considered me a high performing teacher. Which I found to be a bit ridiculous and a complete reversal on the message they continually project. But I think they ridiculous just how crazy my school was, and recognition of the effort I put up in front of those obstacles. I believe there was debate over whether it was even worthwhile to continue to place corps members at my school. I compared ridiculousness notes with other CMAs at Institute this summer. And while most TFA schools have their problems, ours still rank pretty high.

I was also honored in various ways by the school itself. On one of the last days of in-service, Luke and I were both given star quilts--a big honor in Lakota culture. At graduation, the salutatorian thanked the two of us in particular for the work we did for her and her classmates. That's one of the moments from my two years that I'll remember best.

I'm not done with education. Walking into Edison High School yesterday, I felt a tingle of recognition for the parts of teaching I liked: meeting students that are warm and friendly despite all the things that have been stacked against them. I'm already tutoring a girl here, who, though her family is far from struggling financially, reminds me of the same issues I experienced on the rez. She thinks she developmentally incapable of doing the math, but she's not: it's just that no one made her memorize her multiplication tables. At the very least, I'll be writing about education. A few of the teachers I met yesterday told me they would keep me posted on story tips coming out of their schools.

I'm sure there's more to say about how these two years have changed me. But again, that was never the point--and I'm still floating too much now, figuring out what I'm doing, to have a grip on how I changed. Maybe one day soon I'll have a more fitting epilogue.

Watch for a new blog soon, less constrained in topic and updated with more frequency.

I've always struggled with endings. Last summer, I don't think I wrote about the act leaving South Dakota until I actually came back to the state again in the fall. But yesterday, feeling a little bit nostalgic for my Teach For America days, I made my way to Edison High School in North Philly to see how Institute is going in these parts; I figured that was as good an occassion as any to reflect on what happened, and what comes next.

I get the same questions repeatedly. Even the CMAs I talked to yesterday wanted to know: how did I like it? Which is open to broad interpretation, of course. Their follow-up of So you didn't go crazy? makes it a little more clear.

My practiced response--the one that garnered the question on sanity--is that I loved South Dakota, but teaching not so much. I'll certainly miss the inherent adventurousness of my lifestyle in the country, and the people that I adventured with. I won't miss writing tests, or writing lesson plans, or the pressure that came with teaching--or at least the pressure that I put on myself. And I wasn't really there to adventure; I was there to teach.

So perhaps a more important question would be did I teach? I've been indoctrinated by TFA to believe that if the results don't show learning, then there's no teaching. I believe I enumerated the results of my final exams in an earlier post; suffice to say they weren't pretty. During a professional evaluation with my school director at Institute this summer, she remarked that I was sometimes over-critical of my teaching experience. It was feedback I had anticipated, but no matter how I spin the experience, I know I'll never be satisfied with my performance. There was too much more I could have done.

Not to say that there is no positive spin. At my end-of-year conversation, my Program Director told me that despite the low performance of my students, the organization still considered me a high performing teacher. Which I found to be a bit ridiculous and a complete reversal on the message they continually project. But I think they ridiculous just how crazy my school was, and recognition of the effort I put up in front of those obstacles. I believe there was debate over whether it was even worthwhile to continue to place corps members at my school. I compared ridiculousness notes with other CMAs at Institute this summer. And while most TFA schools have their problems, ours still rank pretty high.

I was also honored in various ways by the school itself. On one of the last days of in-service, Luke and I were both given star quilts--a big honor in Lakota culture. At graduation, the salutatorian thanked the two of us in particular for the work we did for her and her classmates. That's one of the moments from my two years that I'll remember best.

I'm not done with education. Walking into Edison High School yesterday, I felt a tingle of recognition for the parts of teaching I liked: meeting students that are warm and friendly despite all the things that have been stacked against them. I'm already tutoring a girl here, who, though her family is far from struggling financially, reminds me of the same issues I experienced on the rez. She thinks she developmentally incapable of doing the math, but she's not: it's just that no one made her memorize her multiplication tables. At the very least, I'll be writing about education. A few of the teachers I met yesterday told me they would keep me posted on story tips coming out of their schools.

I'm sure there's more to say about how these two years have changed me. But again, that was never the point--and I'm still floating too much now, figuring out what I'm doing, to have a grip on how I changed. Maybe one day soon I'll have a more fitting epilogue.

Watch for a new blog soon, less constrained in topic and updated with more frequency.

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Politics

On Friday I drove up to Kadoka to vote early for the South Dakota democratic primary (I'm flying down to Houston on Sunday, so I'll miss the excitement). The county auditor was on lunch break; I decided to walk up to the Jackson County Library to peruse some magazines, but it seemed that the librarian was on lunch break, too. I ended up having to sit around for twenty minutes in the County Courthouse. Just before 1 pm, various county officers paraded back into their various offices from lunch break.

About two weeks ago I took off from school early--I was only going to have three students that afternoon, anyway--to drive down to Pine Ridge to see Bill Clinton speak. He spoke in Mission yesterday; I've heard rumors that Hillary will be speaking in Kyle later this week. Meanwhile, Obama hasn't made it out of the "big cities" in the east of the state.

Bill had a series of talking points tailor made for the reservations: health care (Indian Health Services per patient funds are half of those for federal prisoners); diabetes; education; alternative energy sources. People who caught him in Mission confirmed that he spoke about the same issues there. Clinton did well by Indian County when he was in office. I've lost my notes from his speech, so I can't confirm any of positive policies he put in place, but I do remember him stating that when he visited the same high school gymnasium a decade earlier, he was the first President to visit a reservation since FDR.

Obama seems like the frontrunner for June 3 here in South Dakota; in an April 3 poll, he led Clinton 46% to 34% and NPR recently reported that he is easily out fund raising Clinton here. But a strong turnout of Native American voters could make fund raising numbers irrelevant. I was recently told that Native Americans are the country's most Democratic demographic; given that South Dakota is far from the most Democratic place in the country, if the Clintons can successfully galvanize the Native populations it could be a closer race than people anticipate.

Will the Clinton's strategy of campaigning on the reservations pan out? I mostly know the sympathies of youth here--of my own students, too young to vote, and of the twenty-somethings that are aides in my friends' classrooms--and, as seems true across the country, the youth seem excited about Obama. His "First Americans for Obama" seems to have met with success, too; I recently heard a radio story about how, upon becoming the first Presidential candidate to visit the Crow Nation in Montana, he was "adopted" into the tribe (complete with adoptive parents).

Which is why I'm disappointed that Obama has chosen not to visit us here in South Dakota, too. He may not need South Dakota to win the nomination--and he may not need the Rez vote to win South Dakota--but maybe he will. There is one more week. Are you coming, Barack?

About two weeks ago I took off from school early--I was only going to have three students that afternoon, anyway--to drive down to Pine Ridge to see Bill Clinton speak. He spoke in Mission yesterday; I've heard rumors that Hillary will be speaking in Kyle later this week. Meanwhile, Obama hasn't made it out of the "big cities" in the east of the state.

Bill had a series of talking points tailor made for the reservations: health care (Indian Health Services per patient funds are half of those for federal prisoners); diabetes; education; alternative energy sources. People who caught him in Mission confirmed that he spoke about the same issues there. Clinton did well by Indian County when he was in office. I've lost my notes from his speech, so I can't confirm any of positive policies he put in place, but I do remember him stating that when he visited the same high school gymnasium a decade earlier, he was the first President to visit a reservation since FDR.

Obama seems like the frontrunner for June 3 here in South Dakota; in an April 3 poll, he led Clinton 46% to 34% and NPR recently reported that he is easily out fund raising Clinton here. But a strong turnout of Native American voters could make fund raising numbers irrelevant. I was recently told that Native Americans are the country's most Democratic demographic; given that South Dakota is far from the most Democratic place in the country, if the Clintons can successfully galvanize the Native populations it could be a closer race than people anticipate.

Will the Clinton's strategy of campaigning on the reservations pan out? I mostly know the sympathies of youth here--of my own students, too young to vote, and of the twenty-somethings that are aides in my friends' classrooms--and, as seems true across the country, the youth seem excited about Obama. His "First Americans for Obama" seems to have met with success, too; I recently heard a radio story about how, upon becoming the first Presidential candidate to visit the Crow Nation in Montana, he was "adopted" into the tribe (complete with adoptive parents).

Which is why I'm disappointed that Obama has chosen not to visit us here in South Dakota, too. He may not need South Dakota to win the nomination--and he may not need the Rez vote to win South Dakota--but maybe he will. There is one more week. Are you coming, Barack?

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Posting from school...

...where, twenty minutes ago, a bunch of students broke out into an impromptu water fight in the hallway, throwing water balloons and dumping water bottles on top of one another.

Our Principal's response: hey, that's okay. In fact, it's a good idea! Tomorrow we'll have a school-wide water fight, in which teachers are also fair game!

(If this is true, I will not be coming to school tomorrow, in protest.)

No matter that we're letting students wander the halls at will this afternoon. No matter that students came running into the English room, grabbed five water bottles for use in the fight, and said "F*** you" to the teacher when he tried to contain them. He wrote them up; the Principal told them they did nothing wrong.

We haven't really had discipline all year. But we've tried to look like a school. With four days left, we've stopped doing even that: every day I expect nothing but mayhem, with no attempt to control the kids at all.

Our Principal's response: hey, that's okay. In fact, it's a good idea! Tomorrow we'll have a school-wide water fight, in which teachers are also fair game!

(If this is true, I will not be coming to school tomorrow, in protest.)

No matter that we're letting students wander the halls at will this afternoon. No matter that students came running into the English room, grabbed five water bottles for use in the fight, and said "F*** you" to the teacher when he tried to contain them. He wrote them up; the Principal told them they did nothing wrong.

We haven't really had discipline all year. But we've tried to look like a school. With four days left, we've stopped doing even that: every day I expect nothing but mayhem, with no attempt to control the kids at all.

Thursday, May 08, 2008

A Rant

Usually I mention all of the foibles of school in my running log, because somehow it seems more private and inaccessible. But I've gone this long without being discovered, it seems. With a week and a half of school left, I'm feeling more willing to speak openly. And I need to vent.

I gave my Algebra II final today and I was plugging numbers as a result. I will start out with what is the most important number: my students averaged 48% on the final exam. If I discount the one student who was not with us the entire year and the student who worked for only about five or six days, that number goes up to 60%. Which is not quite as heart-tearingly awful, but is pretty damn miserable itself. (Consider, too, that I lopped 40% off the end of my test because we just didn't manage to cover that material. Which means that is 36% mastery of the material I intended to teach.)

There are many things that can explain those numbers. My own performance as a teacher is obviously one of them. I think it's important for teachers to take responsibility for what happens in their classroom, so I hate to have this next paragraph sound like an excuse. But here goes:

I also ran numbers on attendance in the class. In the first semester, my individual attendance average was 75%. One student made it to 79% of the classes. (Noah, our English teacher, once mentioned that he noticed something somewhere online saying that attendance below 90% is legally considered some form of delinquency). This semester, when things started to go sour, we dropped to 54% attendance.

When running these numbers, I counted only days where I had a student in class: early outs, assemblies, cancellations--these did not count. Nor did the days where simply no one showed up. By this standard, we had 97 days of Algebra II this year (if you count this week and next that will probably go up to 104 days). Our school year is scheduled for 172 days.

Here is what I find most shocking: if I look at the raw number of days that students were actually in Algebra II this year, my student who was in the class the most attended 65 days of class. In the entire year.

What do we do about it: we don't punish students who skip class ("Just fail them," instructs the principal); if our secretary is on maternity leave, we don't even bother to check if absences are excused; our School Information Coordinator refuses to share his attendance data with our Truancy Officer; we cancel school at least once every two weeks, sending a wonderful message about how important school is.

My favorite story about how we encourage good attendance comes from just this week: on Tuesday, there were three elementary school field trips scheduled. We no longer had enough buses to get all the students to school. The solution: anyone on a bus route just doesn't have to come that day. Glad to know we have our priorities straight.

Attendance is only the first issue. Recently we learned we lack sufficient funds to pay all our employees for the rest of the year. Nonessential staff are being cut just so we can keep our doors open. It's unclear where all that money went.

Time to run off this frustration.

I gave my Algebra II final today and I was plugging numbers as a result. I will start out with what is the most important number: my students averaged 48% on the final exam. If I discount the one student who was not with us the entire year and the student who worked for only about five or six days, that number goes up to 60%. Which is not quite as heart-tearingly awful, but is pretty damn miserable itself. (Consider, too, that I lopped 40% off the end of my test because we just didn't manage to cover that material. Which means that is 36% mastery of the material I intended to teach.)

There are many things that can explain those numbers. My own performance as a teacher is obviously one of them. I think it's important for teachers to take responsibility for what happens in their classroom, so I hate to have this next paragraph sound like an excuse. But here goes:

I also ran numbers on attendance in the class. In the first semester, my individual attendance average was 75%. One student made it to 79% of the classes. (Noah, our English teacher, once mentioned that he noticed something somewhere online saying that attendance below 90% is legally considered some form of delinquency). This semester, when things started to go sour, we dropped to 54% attendance.

When running these numbers, I counted only days where I had a student in class: early outs, assemblies, cancellations--these did not count. Nor did the days where simply no one showed up. By this standard, we had 97 days of Algebra II this year (if you count this week and next that will probably go up to 104 days). Our school year is scheduled for 172 days.

Here is what I find most shocking: if I look at the raw number of days that students were actually in Algebra II this year, my student who was in the class the most attended 65 days of class. In the entire year.

What do we do about it: we don't punish students who skip class ("Just fail them," instructs the principal); if our secretary is on maternity leave, we don't even bother to check if absences are excused; our School Information Coordinator refuses to share his attendance data with our Truancy Officer; we cancel school at least once every two weeks, sending a wonderful message about how important school is.

My favorite story about how we encourage good attendance comes from just this week: on Tuesday, there were three elementary school field trips scheduled. We no longer had enough buses to get all the students to school. The solution: anyone on a bus route just doesn't have to come that day. Glad to know we have our priorities straight.

Attendance is only the first issue. Recently we learned we lack sufficient funds to pay all our employees for the rest of the year. Nonessential staff are being cut just so we can keep our doors open. It's unclear where all that money went.

Time to run off this frustration.

Sunday, April 27, 2008

3 Weeks

I'm realizing I've never really left behind a place before: West Hartford will always feel like home, and I will always be back there for a week or so every year. My stint in Haverford last year was my shortest since I arriving at college--at a solid two months. And now I'll be spending another year there. Every few months I seem to hope a plane and head home--to one of my homes. I take note of what new changes have accrued and then fall into easy old rhythms.

My roots in South Dakota feel much less permanent, though: within a year or two, all my close friends here will have picked up and moved on, too, to somewhere else.

When I come out to visit next year, I imagine it will be strangely unlike coming home. For the first time in my life I will be visiting an old home, a place I once lived in and (probably) never will again; revisiting a part of my life, that, unlike even college, won't be truly repeatable again.

It will be strange. I'm already over prone to nostalgia.

My roots in South Dakota feel much less permanent, though: within a year or two, all my close friends here will have picked up and moved on, too, to somewhere else.

When I come out to visit next year, I imagine it will be strangely unlike coming home. For the first time in my life I will be visiting an old home, a place I once lived in and (probably) never will again; revisiting a part of my life, that, unlike even college, won't be truly repeatable again.

It will be strange. I'm already over prone to nostalgia.

South Dakota Weather

For the past two weeks, South Dakota has been at its springtime best: every day I walk out of school with my shirtsleeves rolled up; the sun is shining; even the grass, usually dry and brown, is turning green after the snow. Camping weather, finally.

We made plans to head to Custer. Then I started checking the weather: high of 53 on Saturday. Then a revision: high of 48 on Saturday. High of 42 on Saturday. High of 38 on Saturday. 60% chance of precipitation on Saturday.

So camping turned into cabining.

Saturday turned out be a nice day. It was sunny but cool in the morning. In the afternoon we decided to drive to Little Devil's Tower. My guidebook said it was a hike suitable for families with small children.

When we got in the cars it was 40 degrees out, cold but sunny, a beautiful day. Within the 15 minutes it took us to get into the park, the temperature had dropped to 30. Still nice if you kept moving.

Passing into the rocks.

Passing into the rocks.

The hike was flat at first. Then it started to get steeper. And steeper.

Small children can't climb rocks like this.

Small children can't climb rocks like this.

The top of the hike was great. We were scrambling straight up rock faces. Atop the mountain, we had a view on one side of Cathedral Spires (I think) and on the other Harney Peak. The other side of Harney Peak was lost in a low-lying cloud. A bitter wind blew across the mountain. And as we waited for the stragglers to arrive, the clouds moved closer.

Soon a few tiny bits of snow were swirling in the wind. By the time I made my final ascent, I could not even see the outline of Harney Peak and the Spires were a swirl of mist. Just clouds.

Climbing in the snow.

Climbing in the snow.

Zach enjoying the view and the snow.

Zach enjoying the view and the snow.

Within the twenty minutes we spent on top of the mountain, we found ourselves in a full on blizzard. An inch of snow had accumulated before we made it off the rocks--nearly an inch by the time we made it back to the cars.

And for those keeping score: 65 degrees and sunny today.

Cross reference the first photo to see the changing conditions.

Cross reference the first photo to see the changing conditions.

We made plans to head to Custer. Then I started checking the weather: high of 53 on Saturday. Then a revision: high of 48 on Saturday. High of 42 on Saturday. High of 38 on Saturday. 60% chance of precipitation on Saturday.

So camping turned into cabining.

Saturday turned out be a nice day. It was sunny but cool in the morning. In the afternoon we decided to drive to Little Devil's Tower. My guidebook said it was a hike suitable for families with small children.

When we got in the cars it was 40 degrees out, cold but sunny, a beautiful day. Within the 15 minutes it took us to get into the park, the temperature had dropped to 30. Still nice if you kept moving.

Passing into the rocks.

Passing into the rocks.The hike was flat at first. Then it started to get steeper. And steeper.

Small children can't climb rocks like this.

Small children can't climb rocks like this.The top of the hike was great. We were scrambling straight up rock faces. Atop the mountain, we had a view on one side of Cathedral Spires (I think) and on the other Harney Peak. The other side of Harney Peak was lost in a low-lying cloud. A bitter wind blew across the mountain. And as we waited for the stragglers to arrive, the clouds moved closer.

Soon a few tiny bits of snow were swirling in the wind. By the time I made my final ascent, I could not even see the outline of Harney Peak and the Spires were a swirl of mist. Just clouds.

Climbing in the snow.

Climbing in the snow. Zach enjoying the view and the snow.

Zach enjoying the view and the snow.Within the twenty minutes we spent on top of the mountain, we found ourselves in a full on blizzard. An inch of snow had accumulated before we made it off the rocks--nearly an inch by the time we made it back to the cars.

And for those keeping score: 65 degrees and sunny today.

Cross reference the first photo to see the changing conditions.

Cross reference the first photo to see the changing conditions.

Sunday, April 20, 2008

4 Weeks

Four weeks with students; five weeks at school; six weeks--maybe--in South Dakota.

I'm anticipating the end of my teacherly responsibilities with a good bit of impatience, something I feel somewhat bad about. But then I stop to think about what teacher does not look forward to the summmer? It's one of the perks of the job, really.

Four more weeks with students still seems like a lot of lesson plans and tests and, yes, behavior problems. Seeing the end so close deflates my work ethic: I just wish it was here already (and there will be a lot of work in these four weeks, unfortunately). It's a microcosm of my two-year experience; knowing that there was a best-used-by date on my teaching career made me less invested in a lot of aspects of teaching. I would've done much better, I know, if I had thought of this as an experience with no end.

Only six more weeks in this state, though, seems like a damn short time: that's really six more chances to go camping, to walk through the Badlands, or to hang out with the friends I've met here.

My parents came to visit this weekend, and I took them to some of the local "attractions": we hiked out on Eagle Nest Butte, seven miles south of town, and out at Wolf's Table, in the Badlands seven miles north. We drove 50 miles north to Philip for dinner, the first time I've been to the town; two nights ago we ate at Club 27 in Kadoka, the first time in my two years I've made it there, either. I also talked a lot: told them a lot of the little stories from the past two years that I hadn't shared yet. I've always known that I'd get nostalgic when it came time to leave here; it's in my nature to be wistful about everything I leave behind. Now I'm starting to see where that nostalgia will leak out from, and it's making the littlest experiences--a sunny day, or a drive through a canyon--seem that much more poignant.

I'm anticipating the end of my teacherly responsibilities with a good bit of impatience, something I feel somewhat bad about. But then I stop to think about what teacher does not look forward to the summmer? It's one of the perks of the job, really.

Four more weeks with students still seems like a lot of lesson plans and tests and, yes, behavior problems. Seeing the end so close deflates my work ethic: I just wish it was here already (and there will be a lot of work in these four weeks, unfortunately). It's a microcosm of my two-year experience; knowing that there was a best-used-by date on my teaching career made me less invested in a lot of aspects of teaching. I would've done much better, I know, if I had thought of this as an experience with no end.

Only six more weeks in this state, though, seems like a damn short time: that's really six more chances to go camping, to walk through the Badlands, or to hang out with the friends I've met here.

My parents came to visit this weekend, and I took them to some of the local "attractions": we hiked out on Eagle Nest Butte, seven miles south of town, and out at Wolf's Table, in the Badlands seven miles north. We drove 50 miles north to Philip for dinner, the first time I've been to the town; two nights ago we ate at Club 27 in Kadoka, the first time in my two years I've made it there, either. I also talked a lot: told them a lot of the little stories from the past two years that I hadn't shared yet. I've always known that I'd get nostalgic when it came time to leave here; it's in my nature to be wistful about everything I leave behind. Now I'm starting to see where that nostalgia will leak out from, and it's making the littlest experiences--a sunny day, or a drive through a canyon--seem that much more poignant.

Sunday, April 06, 2008

Stressed

I'm stressed right now. As previously mentioned, I visited the Crow Peak Brewing Company yesterday and talked for a while with Jeff Drumm, the owner and brewer. (It was awesome. Great beer and the coolest bar I've been to in South Dakota.) Today I've been trying to pound the interview into an article. I've got about 700 words written and I'm realizing I have a lot to learn about journalism. Never mind the fact that I have three more brewers to interview yet, at which point I will probably have to rework what I've already got. I've put aside the many other things I need to work on--lesson plans this week, preparatory work for my conference in Houston next weekend, plans for the PLC I am facilitating in two weeks--and spend 5 hours writing this instead. I probably will take a while falling asleep tonight as I work out ways I could improve the thing.

I recently came across Health Magazine's ranking of the most (and least) stressful jobs.

The relevant points:

I'm going to assume my job is just about as stressful as an inner city high school teacher's, for obvious reasons. So I'm moving up in the world! If all goes according to plan, I will no longer have the world's most stressful job--just it's seventh most stressful!

The difference: I'm excited to stay up late and write and edit and rewrite. Making lesson plans? Not so much.

Time to go do some of that other work before my bed calls.

I recently came across Health Magazine's ranking of the most (and least) stressful jobs.

The relevant points:

1. Inner City HS Teacher

...

7. Journalist

I'm going to assume my job is just about as stressful as an inner city high school teacher's, for obvious reasons. So I'm moving up in the world! If all goes according to plan, I will no longer have the world's most stressful job--just it's seventh most stressful!

The difference: I'm excited to stay up late and write and edit and rewrite. Making lesson plans? Not so much.

Time to go do some of that other work before my bed calls.

Tuesday, April 01, 2008

Coming Soon: South Dakota Brewpubs

I may be doing a magazine article on South Dakota's local brewpubs in the near future. Stayed tuned for info and photos on Crow Peak Brewing in Spearfish and the oft-visited Firehouse in Rapid City. I'm hoping to get tours and do interviews this weekend.

Monday, March 31, 2008

Hogsback (Durango, Colorado)

Great Sand Dunes

Rocky Mountains

Thursday, March 27, 2008

Tap the Rockies

And not by drinking Coors Light. That's gross.

For my four-day spring break, I joined a group headed down towards Southwestern Colorado. Originally the trip was sold as a ski-venture, but the discovery that Ska Brewing, a well regarded brewery in this circle, was headquartered in Durango, along with the arrival of spring weather, refocused the intentions of the trip: Colorado, we decided, is the Napa Valley of Beer. And we like beer.

My camera is floating somewhere between here and Mission, so I will have to steal photos from Marion to document the travels.

I headed out soon after parent-teacher conferences ended on Thursday to meet Kim in He Dog and ride with her to Boulder. Our route took me through Wyoming, a state that I had not yet had time to visit. It looked (at least in the corner we ventured through) sort of like Nebraska. Then we pulled into Colorado, which at this point of the night was amazingly flush with traffic and annoying big-box developments. At this point I was not a fan of Colorado.

Our mission on Thursday night was the reach the pub at the Boulder Beer Company, makers of the well-regarded (especially by Cool Zach) Mojo IPA, and Colorado's first microbrewery. Kim and I left about an hour before the rest of the gang, and we arrived in Boulder around 9 PM. Consulting our directions to the pub, we were surprised to find ourselves pulling into an office park. Upon first consideration, though, I realized that this was a beer company first, and a brewpub second, so the location should not have been a surprise. Nor should have their closing time of 9 PM, either, really. So we had to scratch that one. (At various points throughout the trip I bought bottles of some unusual Boulder beers for later consumption.)

After about 45 minutes of wandering through the CU campus, we finally pulled into a Taco Bell and got directions downtown ("Pull out of the parking lot, take a right and keep going."). There we found BJ's Restaruant and Brewpub. I was a bit disappointed to intuit that the place was a chain, because there were 3 or 4 other possibilities to choose from, but the food was good. With my pizza I ordered the sampler of the pub's 7 standard beers: a blonde (one of my least favorite styles), a hefeweizen (not usually one of my favorites, but excellent here); a pale ale; an Irish red; a brown (they called this one a "Tatonka Brown," a butchering of the spelling of "Tatanka," the Lakota word for buffalo); a porter; and an excellent Imperial Stout to finish things off. Just after dinner we got a call from the others that they had arrived and were at the Southern Sun brewpub. After realizing this was about a 15-minute drive away, we were able to get Kate to pick us up. At Southern Sun I tasted the porter that the group had ordered, and then got another sampler to share with the group. I chose some slightly more unusual beers this time: a Wit that was so heavily spiced with chamomile that it tasted like liquid soap, an interesting ginger beer, a honey ale, and a variety of pale ales. Before it got too late, we found our way to a Days Hotel and rested up for the next day of driving.

The next morning we headed out for the mountains, which looked like this:

After about an hour of driving, we stopped for gas in a small town. It was a beautiful day, slightly cold but sunny, and I was surrounded by mountains. Maybe I liked Colorado after all.

At Russ's recommendation, we pulled into Salida for lunch. We came in on a small local highway, and passed a lot of trailers and run-down houses. The place struck me as a hard-on-its-luck mountain town, a beautiful place still struggling to hang on. Then we got to Amica's, our intended restaurant.

Any town with wood-fired pizza and microbrewed beer is probably doing alright. Turns out if you drive in another way, Salida looks like the decently yuppie ski town it really is. What can you do?

Amica's was excellent though. I had a great portabella mushroom sandwich with a dopplebock on the side. Below you will see the beautiful array of colors that our beers offered:

The fellers posed for a photo in Salida.

After driving for a few more hours alongside the Sangre de Cristo mountains, we took a break from beer for our first outdoorsy spot: the Great Sand Dunes National Park.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

As we were repacking the cars after the dunes, a ranger came over asking if we were headed into the backwoods area. Sadly, of course, we were not. We were headed on to Durango, where Darius' father lives. This leg of the trip took us back up into the mountains and over the Continental Divide. The snow was packed thick:

On Saturday morning we got up early to head out on a supposedly "moderate" hike before beginning our tour of Durango's brewers. Russ and I had picked out the Hogsback trail the night before.

The trail turned out to consist of a very steep climb up a barren mountain. Which I thought was awesome. A few times I sprinted up the very sharp inclines. Seeing how others responded to the altitude, it seems that I am lucky that I stay in relatively good shape.

There were some nice views from the top. Turns out Colorado ain't so bad, after all.

Hike completed, we headed to Durango proper. Flipping through the Durango tourist magazine at our hotel, I found an article that confirmed our suspicious: Durango itself is almost officially the Napa Valley of Beers. A town of 15,000 residents, it produces 15,000 barrels of beer per year, and each of its 4 breweries is entirely green.

Our first stop was Carver Brewing Company. Since they do not bottle or distribute their beer, it was an ideal stop for lunch: whatever we wanted to try, we had to try in house.

Being a completist, I, of course, had to try them all. So here I am with my next sampler. So many mini-beers!

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.

After Carver's, we headed to Ska Brewing, Durango's largest brewery. And by largest, I mean it is a small office tucked away in the corner of a small town. When we pulled into the dirt parking lot, a crew of ski bums were sitting around in camp chairs enjoying the sun and beer. Inside, the tasting room was about as hip as you would expect from that name. Lots of homebrewing supplies, too. We almost bought a kit to make an American Pale Ale, but I decided it was overpriced. I took a post-sampler break and just took small sips of what everyone else ordered. I bought a few samplers out of this cooler for later consumption, though.

At the end of the day, the trunk of the other car looked like this. Our trunk was not too different.

On Sunday, Russ, Katie, Darius and I decided to take advantage of our last free day in the Rockies for another hike. Russ is serious about his hiking and planned a 10-mile hike that could be extended into a 13-miler or so, if we were feeling great. The first snag in the plan occured when the road we intended to drive down was closed, meaning we had to join the trail about a mile and a half earlier than planned. We struck out from the head of the Colorado Trail, which winds 480 miles all the way back up to Denver. The hike was spectacular: there were still two or three feet of snow packed on the ground, so we were walking over that. By the earlier afternoon, as things started to warm up, the snow started to soften, and my foot would punch down about a foot with each step, which reminded me that I need to get some more waterproof shoes for hiking. We had intended to reach a waterfall when we got to the top of the climb, but we had misread the map, and that would've required tacking another 7 or so miles onto what was already a 9-mile trek. But we ended up pleasurably exhausted.

Those who chose not to join us on the hike spent the day at another of Durango's brewpubs, Steamworks. And by spent the day, I mean they were there for literally 5 hours. By the time we arrived they were very good friends with the waitstaff, and as more workers got off their shifts, they would join us on the deck to hang out. Apparently they have a tradition of doing stout slammers, which consists of chugging 10 oz. or so of their stout. So we did it. Here is the aftermath:

After leaving Steamworks, we had an excellent dinner at a Himalayan Restaurant before heading to bed early so we could make the 15-hour drive the next day without any real problems.

Sadly the trip home did not involve any brewpubs. We considered stopping in Alamosa at the San Luis Brewery, but it did not fit into our plans. I did buy a bomber of their Mexican Lager at a liquor store, however.

Alamosa has been hit by an alarming number of cases of Salmonella over the past few days; it seemed that the municipal water supply was tainted. When we stopped at a gas station to use the bathroom, we found the water shut off and we had to use hand sanitizer instead. The beers stores were taking full advantage of the crisis, though. We passed one, on the way out of town, that gave the perfect solution: "Can't drink the water? Have a beer."

Fair enough.

For my four-day spring break, I joined a group headed down towards Southwestern Colorado. Originally the trip was sold as a ski-venture, but the discovery that Ska Brewing, a well regarded brewery in this circle, was headquartered in Durango, along with the arrival of spring weather, refocused the intentions of the trip: Colorado, we decided, is the Napa Valley of Beer. And we like beer.

My camera is floating somewhere between here and Mission, so I will have to steal photos from Marion to document the travels.

I headed out soon after parent-teacher conferences ended on Thursday to meet Kim in He Dog and ride with her to Boulder. Our route took me through Wyoming, a state that I had not yet had time to visit. It looked (at least in the corner we ventured through) sort of like Nebraska. Then we pulled into Colorado, which at this point of the night was amazingly flush with traffic and annoying big-box developments. At this point I was not a fan of Colorado.

Our mission on Thursday night was the reach the pub at the Boulder Beer Company, makers of the well-regarded (especially by Cool Zach) Mojo IPA, and Colorado's first microbrewery. Kim and I left about an hour before the rest of the gang, and we arrived in Boulder around 9 PM. Consulting our directions to the pub, we were surprised to find ourselves pulling into an office park. Upon first consideration, though, I realized that this was a beer company first, and a brewpub second, so the location should not have been a surprise. Nor should have their closing time of 9 PM, either, really. So we had to scratch that one. (At various points throughout the trip I bought bottles of some unusual Boulder beers for later consumption.)

After about 45 minutes of wandering through the CU campus, we finally pulled into a Taco Bell and got directions downtown ("Pull out of the parking lot, take a right and keep going."). There we found BJ's Restaruant and Brewpub. I was a bit disappointed to intuit that the place was a chain, because there were 3 or 4 other possibilities to choose from, but the food was good. With my pizza I ordered the sampler of the pub's 7 standard beers: a blonde (one of my least favorite styles), a hefeweizen (not usually one of my favorites, but excellent here); a pale ale; an Irish red; a brown (they called this one a "Tatonka Brown," a butchering of the spelling of "Tatanka," the Lakota word for buffalo); a porter; and an excellent Imperial Stout to finish things off. Just after dinner we got a call from the others that they had arrived and were at the Southern Sun brewpub. After realizing this was about a 15-minute drive away, we were able to get Kate to pick us up. At Southern Sun I tasted the porter that the group had ordered, and then got another sampler to share with the group. I chose some slightly more unusual beers this time: a Wit that was so heavily spiced with chamomile that it tasted like liquid soap, an interesting ginger beer, a honey ale, and a variety of pale ales. Before it got too late, we found our way to a Days Hotel and rested up for the next day of driving.

The next morning we headed out for the mountains, which looked like this:

After about an hour of driving, we stopped for gas in a small town. It was a beautiful day, slightly cold but sunny, and I was surrounded by mountains. Maybe I liked Colorado after all.

At Russ's recommendation, we pulled into Salida for lunch. We came in on a small local highway, and passed a lot of trailers and run-down houses. The place struck me as a hard-on-its-luck mountain town, a beautiful place still struggling to hang on. Then we got to Amica's, our intended restaurant.

Any town with wood-fired pizza and microbrewed beer is probably doing alright. Turns out if you drive in another way, Salida looks like the decently yuppie ski town it really is. What can you do?

Amica's was excellent though. I had a great portabella mushroom sandwich with a dopplebock on the side. Below you will see the beautiful array of colors that our beers offered:

The fellers posed for a photo in Salida.

After driving for a few more hours alongside the Sangre de Cristo mountains, we took a break from beer for our first outdoorsy spot: the Great Sand Dunes National Park.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.As we were repacking the cars after the dunes, a ranger came over asking if we were headed into the backwoods area. Sadly, of course, we were not. We were headed on to Durango, where Darius' father lives. This leg of the trip took us back up into the mountains and over the Continental Divide. The snow was packed thick:

On Saturday morning we got up early to head out on a supposedly "moderate" hike before beginning our tour of Durango's brewers. Russ and I had picked out the Hogsback trail the night before.

The trail turned out to consist of a very steep climb up a barren mountain. Which I thought was awesome. A few times I sprinted up the very sharp inclines. Seeing how others responded to the altitude, it seems that I am lucky that I stay in relatively good shape.

There were some nice views from the top. Turns out Colorado ain't so bad, after all.

Hike completed, we headed to Durango proper. Flipping through the Durango tourist magazine at our hotel, I found an article that confirmed our suspicious: Durango itself is almost officially the Napa Valley of Beers. A town of 15,000 residents, it produces 15,000 barrels of beer per year, and each of its 4 breweries is entirely green.

Our first stop was Carver Brewing Company. Since they do not bottle or distribute their beer, it was an ideal stop for lunch: whatever we wanted to try, we had to try in house.

Being a completist, I, of course, had to try them all. So here I am with my next sampler. So many mini-beers!

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.After Carver's, we headed to Ska Brewing, Durango's largest brewery. And by largest, I mean it is a small office tucked away in the corner of a small town. When we pulled into the dirt parking lot, a crew of ski bums were sitting around in camp chairs enjoying the sun and beer. Inside, the tasting room was about as hip as you would expect from that name. Lots of homebrewing supplies, too. We almost bought a kit to make an American Pale Ale, but I decided it was overpriced. I took a post-sampler break and just took small sips of what everyone else ordered. I bought a few samplers out of this cooler for later consumption, though.

At the end of the day, the trunk of the other car looked like this. Our trunk was not too different.

On Sunday, Russ, Katie, Darius and I decided to take advantage of our last free day in the Rockies for another hike. Russ is serious about his hiking and planned a 10-mile hike that could be extended into a 13-miler or so, if we were feeling great. The first snag in the plan occured when the road we intended to drive down was closed, meaning we had to join the trail about a mile and a half earlier than planned. We struck out from the head of the Colorado Trail, which winds 480 miles all the way back up to Denver. The hike was spectacular: there were still two or three feet of snow packed on the ground, so we were walking over that. By the earlier afternoon, as things started to warm up, the snow started to soften, and my foot would punch down about a foot with each step, which reminded me that I need to get some more waterproof shoes for hiking. We had intended to reach a waterfall when we got to the top of the climb, but we had misread the map, and that would've required tacking another 7 or so miles onto what was already a 9-mile trek. But we ended up pleasurably exhausted.

Those who chose not to join us on the hike spent the day at another of Durango's brewpubs, Steamworks. And by spent the day, I mean they were there for literally 5 hours. By the time we arrived they were very good friends with the waitstaff, and as more workers got off their shifts, they would join us on the deck to hang out. Apparently they have a tradition of doing stout slammers, which consists of chugging 10 oz. or so of their stout. So we did it. Here is the aftermath:

After leaving Steamworks, we had an excellent dinner at a Himalayan Restaurant before heading to bed early so we could make the 15-hour drive the next day without any real problems.

Sadly the trip home did not involve any brewpubs. We considered stopping in Alamosa at the San Luis Brewery, but it did not fit into our plans. I did buy a bomber of their Mexican Lager at a liquor store, however.

Alamosa has been hit by an alarming number of cases of Salmonella over the past few days; it seemed that the municipal water supply was tainted. When we stopped at a gas station to use the bathroom, we found the water shut off and we had to use hand sanitizer instead. The beers stores were taking full advantage of the crisis, though. We passed one, on the way out of town, that gave the perfect solution: "Can't drink the water? Have a beer."

Fair enough.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

"The past is never dead. It's not even past."

Today, in a speech that some are already calling historic, Barack Obama cited the above line of William Faulkner's (though he ended up paraphrasing a bit).

The point is that our country cannot so quickly be absolved of what Obama calls our "original sin" of slavery.

From my lens out here in Indian Country, it is clear to me while slavery might be our country's original sin, it is not our only one. For most in this country, it is easy to forget that once, where our communities now stand, there were other communities, other civilizations. Sadly, many of those Indian communities truly are gone; but not all of them are. And the problems those in Indian Country face, too, can be directly traced to the brutal actions of expanding America.

Obama's speech, of course, was in reaction to the recent widespread coverage of Reverend Jeremiah Wright's incendiary sermons. Obama, once accused of not being black enough, is now being called upon to distance himself from what some call "black anger."

I spend a lot of time on the running website Letsrun.com, and it is especially its anonymous message boards. While a self-selected collection of running web-geeks is hardly an accurate cross section of America, the anonymity of the website allows users to express viewpoints that they might not usually.

Some reactions to Obama's speech:

Or this:

*

The point is that our country cannot so quickly be absolved of what Obama calls our "original sin" of slavery.

[W]e . . . need to remind ourselves that so many of the disparities that exist in the African-American community today can be directly traced to inequalities passed on from an earlier generation that suffered under the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

From my lens out here in Indian Country, it is clear to me while slavery might be our country's original sin, it is not our only one. For most in this country, it is easy to forget that once, where our communities now stand, there were other communities, other civilizations. Sadly, many of those Indian communities truly are gone; but not all of them are. And the problems those in Indian Country face, too, can be directly traced to the brutal actions of expanding America.

Obama's speech, of course, was in reaction to the recent widespread coverage of Reverend Jeremiah Wright's incendiary sermons. Obama, once accused of not being black enough, is now being called upon to distance himself from what some call "black anger."

I spend a lot of time on the running website Letsrun.com, and it is especially its anonymous message boards. While a self-selected collection of running web-geeks is hardly an accurate cross section of America, the anonymity of the website allows users to express viewpoints that they might not usually.

Some reactions to Obama's speech:

What was disappointing to me is that there wasn't a stronger repudiation of black anger. If and when people are serious about moving ahead, that will have to be left behind. I don't think he can be taken seriously as a uniter until he bridges that divide.

Or this:

As long as there is a segment of the population who wants to feed off of ridiculous conspiracy theories and blame everything on whitey, then there will be no progress for that group. . . . Despite years of welfare, education programs, affirmative action, and other entitlements, black americans for the most part have not been able to move out of the ghetto both literally and figuratively. . . . The notion that there is a white bogeyman out there keeping blacks down is not only laughable, its harmful.

*

These black Americans stuck in their ghettos are, to commentators like this, the most obvious symbols of this anger. But to call it "black anger" is too limiting, as if it is always emanates from one group, always focuses on another. There is plenty of anger in this community; I have had students curse me out as "whitey"; there have been teachers driven out of my school because of they have overstepped delicate racial lines. But this anger is not a symptom of some racial conspiracy theory, and it emanates in all directions. Nearly every other day, girls at school are fighting viciously. I had a student today whose anger, according to our counselor, was self-directed: he was angry that he could not do the work as well as other students.

More appropriately, then, this might be called the anger of the powerless. And powerlessness knows no racial--or national--boundaries. As Obama has observed elsewhere, "the desperation and disorder of the powerless . . . twists the lives of children on the streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, in much the same way as it does the lives of children on Chicago's South Side or the lives of many children of the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota." In his speech today, he noted that is an anger shared by whites who feel powerless, too, and believe they have lost out on opportunities due to affirmative action for wrongs they and their families never committed.

To call this the anger of the powerless, though, is to give it legitimacy: it is to claim that some are still powerless, to claim that the tragedies of the past are not dead. It is to state that society at large is still accountable for this powerlessness, and that it is not so easy as just telling people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Not everyone is willing to take that kind of responsibility.

So the kind of anger that many of my students and their parents have does, as Obama states about the African-American community, keep them "from squarely facing [their] own complicity in [their] condition," from realizing how the drugs they take and the gangs they join only exacerbate their troubles.

But, as Obama states, "the anger is real; it is powerful; and to simply wish it away, to condemn it without understanding its roots, only serves to widen the chasm of misunderstanding that exists between the races." To blame "black anger" or "Latino anger" or "Indian anger" for the struggles in poor urban and rural communities is simply the inverse of the anger being condemned: the anger throws all blame on "white America" and our response throws it right back. That volley will never end.

If these issues are to be solved, it will require someone stepping out of that cycle of blame. Someone--anyone, the privileged or the poor--taking accountability for the problems, and working patiently to solve them while waiting patiently for the "other side" take accountability, too. One person (one student?) at a time.

Or, to put it in Obama's words:

More appropriately, then, this might be called the anger of the powerless. And powerlessness knows no racial--or national--boundaries. As Obama has observed elsewhere, "the desperation and disorder of the powerless . . . twists the lives of children on the streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, in much the same way as it does the lives of children on Chicago's South Side or the lives of many children of the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota." In his speech today, he noted that is an anger shared by whites who feel powerless, too, and believe they have lost out on opportunities due to affirmative action for wrongs they and their families never committed.

To call this the anger of the powerless, though, is to give it legitimacy: it is to claim that some are still powerless, to claim that the tragedies of the past are not dead. It is to state that society at large is still accountable for this powerlessness, and that it is not so easy as just telling people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Not everyone is willing to take that kind of responsibility.

*

I hate to blame the community for the problems I have experienced at school, but I have a strong belief that the educational problems I have observed on the reservation will not be solved until the families I serve take more responsibility for their children's education. To learn students need to actually be in school; they need to be encouraged to do their homework; parents need to stay in close contact with their children's teachers. None of this happens at my school. Attendance is currently averaging around 60%, at my best guess; if previous experience is any indication, I will most likely see three or four parents at conferences tomorrow night.So the kind of anger that many of my students and their parents have does, as Obama states about the African-American community, keep them "from squarely facing [their] own complicity in [their] condition," from realizing how the drugs they take and the gangs they join only exacerbate their troubles.

But, as Obama states, "the anger is real; it is powerful; and to simply wish it away, to condemn it without understanding its roots, only serves to widen the chasm of misunderstanding that exists between the races." To blame "black anger" or "Latino anger" or "Indian anger" for the struggles in poor urban and rural communities is simply the inverse of the anger being condemned: the anger throws all blame on "white America" and our response throws it right back. That volley will never end.

If these issues are to be solved, it will require someone stepping out of that cycle of blame. Someone--anyone, the privileged or the poor--taking accountability for the problems, and working patiently to solve them while waiting patiently for the "other side" take accountability, too. One person (one student?) at a time.

Or, to put it in Obama's words:

It requires all Americans to realize that your dreams do not have to come at the expense of my dreams; that investing in the health, welfare, and education of black and brown and white children will ultimately help all of America prosper.

In the end, then, what is called for is nothing more, and nothing less, than what all the world's great religions demand - that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us. Let us be our brother's keeper, Scripture tells us. Let us be our sister's keeper. Let us find that common stake we all have in one another, and let our politics reflect that spirit as well.

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Sheep Mountain Table

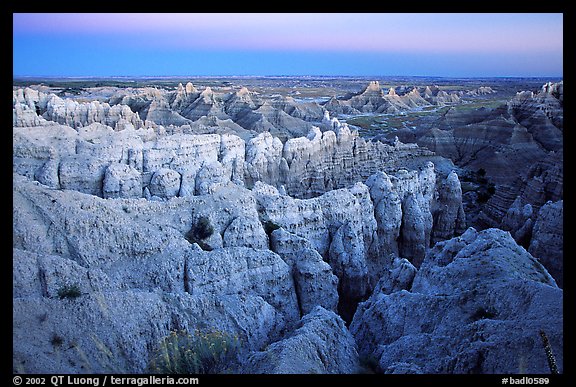

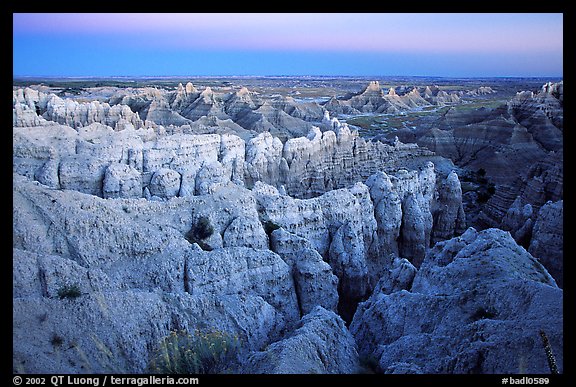

The Badlands are aptly named: they are bad. I did a Google search for "Sheep Mountain Table," where Kim, Matt, and I went hiking yesterday, which netted me the following image:

It also netted me the notes of a court case detailing the death of a 17-year-old who fell from a ledge and the story of a successful search-and rescue operation after a drunken man stumbled who had fallen from a ledge at Bombing Range Overlook.

Then there is that name right there: during World War II, the U.S. Air Force seized some land from tribal members for use as a gunnery range. According to a ranger I met this summer, 99% of the ordnances have been cleared. "But you should NOT go exploring out there," he cautioned.

I don't think we were within the gunnery range. But it's boundaries aren't clear to me (nor, apparently, were they clear to some of the bombers, as a church and post office in Interior "received six-inch shells through the roof," according to Wikipedia).

One of the facts in the deposition for the court case I mentioned is that "There were no warning signs posted in the area and no gate prevented access to the road leading up to the top of the table." In "Desert Solitaire," Edward Abbey argues for the removal of pavement and warning signs and railings in our national parks. The wilderness is a dangerous place, and we should keep it wild.

I tend to agree. Which is why we set out down the crevice of that very same table, gingerly following the path of erosion through the rock and dirt to the valley at the bottom. A month or so ago, Zach and Darius found shell casings in a similar area, but I didn't see any: I came across a few sets of fossilized teeth, a lot of bison turds, and--the sole evidence of the goverment's foray into these lands--a few small pieces of scrap metal, rusted and covered in dirt.

View Larger Map

It also netted me the notes of a court case detailing the death of a 17-year-old who fell from a ledge and the story of a successful search-and rescue operation after a drunken man stumbled who had fallen from a ledge at Bombing Range Overlook.

Then there is that name right there: during World War II, the U.S. Air Force seized some land from tribal members for use as a gunnery range. According to a ranger I met this summer, 99% of the ordnances have been cleared. "But you should NOT go exploring out there," he cautioned.

I don't think we were within the gunnery range. But it's boundaries aren't clear to me (nor, apparently, were they clear to some of the bombers, as a church and post office in Interior "received six-inch shells through the roof," according to Wikipedia).

One of the facts in the deposition for the court case I mentioned is that "There were no warning signs posted in the area and no gate prevented access to the road leading up to the top of the table." In "Desert Solitaire," Edward Abbey argues for the removal of pavement and warning signs and railings in our national parks. The wilderness is a dangerous place, and we should keep it wild.

I tend to agree. Which is why we set out down the crevice of that very same table, gingerly following the path of erosion through the rock and dirt to the valley at the bottom. A month or so ago, Zach and Darius found shell casings in a similar area, but I didn't see any: I came across a few sets of fossilized teeth, a lot of bison turds, and--the sole evidence of the goverment's foray into these lands--a few small pieces of scrap metal, rusted and covered in dirt.

View Larger Map

Saturday, March 15, 2008

St. Patty's Day

I spent the night in Rapid City. Kim left her car parked on Main Street and this morning when we were trying to make our way back there, on every corner the road was blocked by police. Soon the sound of bagpipes alerted us to the fact that it was Rapid City's St. Patrick's Day Parade. There was an assortment of participants: people in pick-up trucks tossing out lollipops, guys dressed up in Leprechaun suits handed out Tootsie Rolls, and a greenish-looking firetruck tossing more candy. My favorite was the grown man in what amounted to an oversized toy car, about the size of his body, which he was capable of driving (and from which he handed out even more candy). Spectatorship was thin, and within 5 minutes the crowd had dispersed, and we got in the car and drove away.

Sunday, March 09, 2008

Animals in Road, Part 3

10:25 AM, ~10 miles east of Wanblee: flock of around 12 large wild turkeys walking leisurely across the road.

Thursday, March 06, 2008

Small Towns

On Tuesday I stopped by the post office to mail out an application to an internship. I was in a bit of a hurry because I was on my way to an interview in Mission. After I had paid for a document mailer and postage and had gotten back into my car, I remembered the materials had to arrive by Friday. So I had to go back in and pull everything out of the mailer and switch over to the Express rate. As I was doing so, I thought about the postage I had already paid, and thought "oh well, it's a couple cents. . . No time to try to get it back now."

Today I was checking the mail and there was an unposted envelope in the box with my name on it. I figured it was the confirmation of my application being sent. But it turned out to be 32 cents of stamps with a sticky note saying that it was reimbursement for the postage I hadn't used.

Today I was checking the mail and there was an unposted envelope in the box with my name on it. I figured it was the confirmation of my application being sent. But it turned out to be 32 cents of stamps with a sticky note saying that it was reimbursement for the postage I hadn't used.

Wednesday, March 05, 2008

Poverty

I learned recently that Allen, South Dakota is the single poorest community in the United States. It's somewhat hard to conceptualize. To me, Allen is no different from any of the other communities around here: it's where I go to do free laundry, or where Shannon goes to get kale for her soup (Kate keeps her fridge well stocked). Then again, all I really know is teacher housing.

The per capita income in Allen is $1,539. It would not be hard for me to blow through that money in a weekend. In fact, when my car needed repairs, I did. The median income for males in Allen is $0.

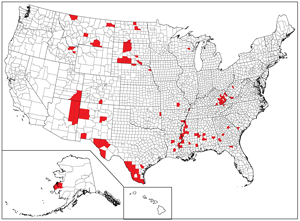

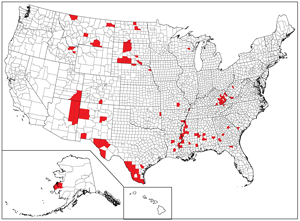

Wanblee is 59th on the list, with almost three times the per capita income of Allen. Fourteen other towns in South Dakota make the top 100, all of which are on or near reservations. The rest of the list is filled with other reservation towns in other states, border towns in Texas, and scattered rural communities across the country. A map of the country's poorest county's makes this pattern clear: Rez towns, border towns, Appalachia, Mississippi Delta--and then just a few scattered outliers. (Shannon County, the bulk of Pine Ridge Reservation is the 2nd poorest county; Todd County, which comprises the Rosebud Reservation, is number 5; Jackson County, where I live, is number 23--though half lies off the reservation. Five of the ten poorest counties are in South Dakota.)

The smallest town on the list has a population of seven (it's in South Dakota!); only one town has more than 10,000 people--and its over twice the size of the second largest community on the list. That rural places dominate the list is no real surprise: I'm sure there are seven people clustered in every major city that have a per capita income less than Aurora Center's ($4,700), but they do not have the distinction of forming their own town, and therefore their own census designated place.

But to discredit these rural people is unfair. I live smack dab in the middle of a red patch above; I would have to drive seventy miles to make it out. And I'm lucky that I can make that drive. Most people here can't. And we're lucky that we have a high school here, not just for the education, but for the jobs: what sets us apart from Allen, and from Wounded Knee, and Parmelee, and Porcupine, and all the other towns I know of just a little below us on the list, is that we have a high school, and therefore a few more jobs, and therefore a few more dollars. But plenty are left jobless, with few models of success available. Unlike the city, there is no starkly different life just a few miles away--only more poverty.

What is striking to me, though, is how little I notice it all. I live in teacher housing; my neighbors, like me, are the lucky few with jobs. I rarely have business in Old Housing, across the highway, and so rarely pass through it. People come by my house selling all kinds of items--dreamcatchers, kittens, elk antlers, government commodities, or even just asking for gas money--but not for their intrusion, I could pretend I lived in some other small town, struggling but fine. I have satellite television. I have wireless internet. I have organic peanut butter--I have kale from the poorest place in America. And I still, after two years, have very little idea what lives my students are living.

The per capita income in Allen is $1,539. It would not be hard for me to blow through that money in a weekend. In fact, when my car needed repairs, I did. The median income for males in Allen is $0.

Wanblee is 59th on the list, with almost three times the per capita income of Allen. Fourteen other towns in South Dakota make the top 100, all of which are on or near reservations. The rest of the list is filled with other reservation towns in other states, border towns in Texas, and scattered rural communities across the country. A map of the country's poorest county's makes this pattern clear: Rez towns, border towns, Appalachia, Mississippi Delta--and then just a few scattered outliers. (Shannon County, the bulk of Pine Ridge Reservation is the 2nd poorest county; Todd County, which comprises the Rosebud Reservation, is number 5; Jackson County, where I live, is number 23--though half lies off the reservation. Five of the ten poorest counties are in South Dakota.)

The smallest town on the list has a population of seven (it's in South Dakota!); only one town has more than 10,000 people--and its over twice the size of the second largest community on the list. That rural places dominate the list is no real surprise: I'm sure there are seven people clustered in every major city that have a per capita income less than Aurora Center's ($4,700), but they do not have the distinction of forming their own town, and therefore their own census designated place.

But to discredit these rural people is unfair. I live smack dab in the middle of a red patch above; I would have to drive seventy miles to make it out. And I'm lucky that I can make that drive. Most people here can't. And we're lucky that we have a high school here, not just for the education, but for the jobs: what sets us apart from Allen, and from Wounded Knee, and Parmelee, and Porcupine, and all the other towns I know of just a little below us on the list, is that we have a high school, and therefore a few more jobs, and therefore a few more dollars. But plenty are left jobless, with few models of success available. Unlike the city, there is no starkly different life just a few miles away--only more poverty.

What is striking to me, though, is how little I notice it all. I live in teacher housing; my neighbors, like me, are the lucky few with jobs. I rarely have business in Old Housing, across the highway, and so rarely pass through it. People come by my house selling all kinds of items--dreamcatchers, kittens, elk antlers, government commodities, or even just asking for gas money--but not for their intrusion, I could pretend I lived in some other small town, struggling but fine. I have satellite television. I have wireless internet. I have organic peanut butter--I have kale from the poorest place in America. And I still, after two years, have very little idea what lives my students are living.

Trashpile

Jossi is highly entertained that I have a run called "Trashpile." The view approaching the trashpile can be seen above.

Tuesday, March 04, 2008

Lost Identities